Crimea is now an autonomous republic of Ukraine, but at the time of the War it was part of the Russian Empire. Its significance lay in the deep harbour of Sevastopol (in those days more usually transcribed as ‘Sebastopol’) which was then the headquarters of the Black Sea Fleet – the target of the Allied Expedition of 1854.

Part of the Black Sea Fleet (including its nuclear submarines) is still based there to this day, which is one reason the area has until recently been closed to visitors from the West. Photographs of landmarks are therefore rare, so I’m posting some of those I’ve taken myself on research trips as they may be of interest to readers of ‘Into the Valley of Death’.

The characters in the novel land with the Allied Fleet at Eupatoria and march down towards Sevastopol.

The stretch where the British landed was called Kalamita Bay, a largely featureless beach with low cliffs in places no higher than a mud bank. This is what it looks like now.

The salt lake mentioned in contemporary reports is still there, within a few feet of the path from the beach. This is where Joe Sullivan encounters something unpleasant in Chapter 2.

But not everything is as it was.

The River Bulganek where our heroes first confront the enemy has dried to nothing, and this is all that now remains to be seen of the crossing on the Post Road to Sevastopol.

The River Alma has fared better, and in wet weather would be almost impossible to ford. Here is the site where the Guards Brigade crossed on 20th September 1854.

You can still see the bank above that sheltered the British from the Russian cannon.

There is a memorial to the Russian soldiers who fell at the Alma at the site of the Greater Redoubt, where Ryder and ‘Ginger’ fight side by side in the novel. The faint mound crested by a low wall at the bottom of this rather wonky picture is all that remains today of the earthworks thrown up to protect the position.

The trees have grown since 1854, and at the time of the battle there was no cover here at all.

Nor was there for the British Army, and this view from the memorial shows how exposed they would have been to the Russians in the Redoubt as they lay in the fields below. The mound of the earthworks is clearer here, visible just below the little wall across the centre of the picture.

Most of those buildings are new too, where the original villages of Bourliouk and Almatamack have grown and spread.

What has not changed, however, is the topography, and this view taken from east of Bourliouk gives at least some idea of how steep a climb it would have been up to the Heights of the Alma – especially in full pack, under a hot sun, and being shot at the whole way.

Some buildings are unchanged too, and (according to the locals) this is the house where Lord Raglan spent the night after the Battle of the Alma.

Those curvy orange tiles are highly characteristic of the local architecture, and Ryder notices them later in both Balaklava and Kadikoi.

(The tiles on the right are modern, and I rather suspect the satellite dish is too...)

Balaklava itself has changed enormously, although the bends in the narrow harbour entrance are still immediately recognizable to students of the war.

The headland to the left, a section of which is seen more clearly below, is where Captain Barker’s ‘W’ battery fire the crucial shot in the fictional attack on the harbour in ‘Into the Valley of Death’.

This picture is taken from the road where Angelo walks away from Ryder to the Bulgar’s farm, and also shows the ruins of the Genoese fortress where Mackenzie sees the attacking Russian sailors.

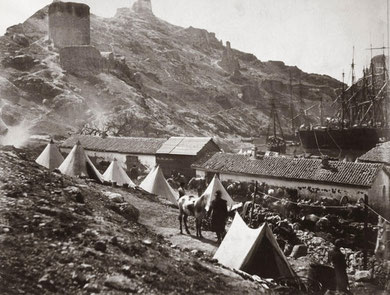

A clearer idea of how it looked at the time is given by Roger Fenton’s photographs of 1855, which show a town ravaged by military occupation. This one, for instance, shows both the Genoese ruins and also the tents pitched ‘in the dirt’ described by Ryder.

This one, from further back, also shows the forest of ‘skeletal masts’ described by Ryder on his first visit.

But even Fenton’s pictures are too late to show us some of the reality of 1854. Here, for instance, is the cavalry camp at Balaklava taken in the late spring of 1855, but none of these huts had yet been erected when Ryder and ‘Polly’ Oliver were living there. The camp position is itself different, since this is the one adopted after the Charge, when the cavalry were moved much nearer the Col.

The site of the Battle of Balaklava itself remains, and through the vineyards it is still possible to see the route down which the Light Brigade charged on 25th October 1854.

This is the ‘Valley of Death’ – which should NOT be confused with the track near the siegeworks at Sevastopol, which was nicknamed the ‘Valley of the Shadow of Death’ and famously photographed by Roger Fenton to show cannon balls in the road. That has an entirely different significance, which I’m hoping to show in a later book.

The village of Kamara also still exists, although many of the houses have fallen into ruin. Enough remains to see the variety to which Sally Jarvis refers, from the rustic shacks to the grand houses, many concealed behind trees and high hedges in the folds of the hills.

Sevastopol itself, however, looks even better than it did in 1854 - despite enduring through a second prolonged siege and bombardment in World War II.

Here, for instance, are the pillars at the landing stage at the 'Grafskaya', which so impressed Ryder when he disembarked with Jarvis.

Here are some of the long straight streets of the Korabelnaya, lined with white-walled barracks just as in Ryder's day...

... and looking every bit as intimidating!

The outer defences of Sevastopol have long been absorbed into what is now a modern and prosperous town, but remnants of all the great bastions remain, cheek by jowl with ordinary houses and regular life. Here, for instance, is part of the wall encircling the Little Redan, which overlooks the road Ryder has to travel by in the book.

Sadly, the original houses by the bastions were mostly destroyed in the various bombardments. The one in which my characters take refuge behind the Little Redan would have looked much like these by the Malakhov, photographed in 1855.

The bastions, however, have a much greater part to play in the next instalment of Ryder's adventures, so I won't go into more detail here.

More immediately relevant to 'Into the Valley of Death' is the track leading from the town into the Careenage Ravine - the route taken by the Russian army at the Battle of Little Inkerman, and again at Inkerman itself. The 'hub of paths' noticed by Ryder is now immaculately kept and marked by neat kerbs, but the crossroads still performed the same function back in 1854.

Here - and unchanged - is the arch under which our heroes had to pass.

Turning right out of the arch, Ryder would have walked towards the camera here, with the Careenage Bay on his left.

The 'under-road' column of Russian marines that left Sevastopol on 26th October travelled by a different route - down the Careenage Ravine itself. There were fewer trees then and hardly any houses, but still this picture gives some idea of the depth and extent of the ravine at its start.

Where the ravine is less overgrown, it is still possible to see the flaking layers of rock which formed the caves from which sharpshooters operated on both sides.

Some of these are extensive, and I imagined it would be from caves like these that Ryder and his friends were ambushed in the ravine.

Unfortunately there is little left to see of the battlefield of Inkerman itself. The site of the British camps is almost entirely built over, and where the landmark 'Windmill' used to be there is now only a roadside garage.

But again, topography does not change, and this picture shows the path towards St Clement's Ravine as it would have been seen from the Russian side. The slope on the right is Inkerman Tusk, and the one on the left leads up to the site of the 'Sandbag Battery'.

This closer view shows the steepness of St Clement's Ravine. The slab of rock to the left is a natural feature, and may be part of what eyewitnesses referred to as the 'ledge' behind which the Russians could shelter before returning to the attack.

This picture was taken from the top of the Sandbag Battery. The wall is relatively modern, but is laid on a natural rise and probably marks the perimeter of the original sandbags. The tree-line in front also shows a definite drop, and this too could have given the Russians a bank under which to shelter and regroup.

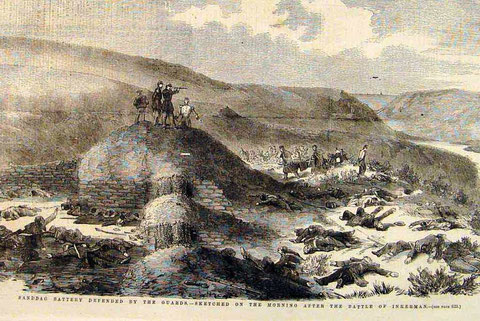

On top of the Sandbag Battery is this strange mound, obviously man-made and grassed over. I was puzzled as to its identity until I remembered the picture below, taken from the Illustrated London News.

This engraving is supposedly taken from a sketch made the morning after the Battle of Inkerman - and in the middle of the enclosure we can clearly see the mound of a magazine. It seems unlikely so sophisticated a construction would have been made for a temporary battery - but decidedly sensible, given the fate of the French battery at Mont Rodolphe. I've therefore assumed the magazine really WAS there at the time of the battle, and it's referred to several times in the novel.

There is obviously much more to see of Ryder's Crimea than these few images - but I'm afraid they will have to wait until the next book, when the Siege of Sebastopol begins in earnest...