The main characters of Into the Valley of Death are fictional - four men who meet in a rainstorm and pass the evening in a game of cards.

Ryder and the young idealistic Charlie 'Polly' Oliver are both in the Light Brigade, members of the 13th Light Dragoons. Niall Mackenzie is of the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders, while Dennis Woodall would describe himself as being one of Her Majesty's Grenadier Guards. They are an unlikely group, but the accidental combination of these regiments not only provides the key to unravelling a mystery within the British Army, but also gives us a unique set of windows through which we can see the major highlights of the first months in the Crimea.

Most paintings of the Charge of the Light Brigade focus on the front-line regiment of 17th Lancers - and indeed, even the cover of 'Into the Valley of Death' adopts the same policy.

However, the 13th Light Dragoons were also in the front line of the Charge, and their role was no less heroic. Only their appearence was less picturesque - which is perhaps why John Charlton's painting Into the Valley of Death depicts them in the distinctive chapska of the 17th Lancers instead of the more conventional shakos they would actually have worn.

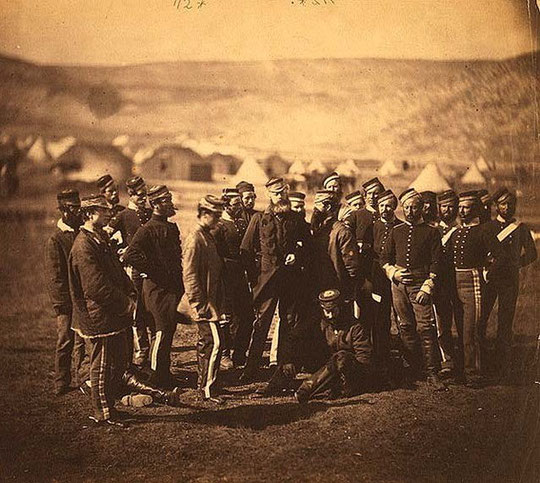

But they were there, they hit the Don Cossack battery at the same time as the Lancers, and they suffered equally intolerable losses. Indeed, one of the most iconic images of the war is this Roger Fenton photograph depicting members of the 13th Light Dragoons who survived the Charge of the Light Brigade.

The tall bearded man in the centre of the group (just to the left of the seated man) is Lt. Col Charles Edmund Doherty, Ryder's commanding officer and a very significant character in the novel.

Doherty (obviously) really existed, but he has a personal as well as a military role to play in the book, and his relationship with Ryder will be the pivot on which their success or failure will depend.

A number of other 'real' characters in the cavalry are depicted in Into the Valley of Death.

This, for instance, is 'Old Look-On', George Bingham, Earl of Lucan, the bulldog-jawed commander of the cavalry in the Crimea.

Even better known is his brother-in-law Lord Cardigan, commander of the Light Brigade itself. Cardigan makes several crucial appearences in the book, and it is not for nothing that Ryder refers to him as 'James Brudenell, Earl of Cardigan, a man with the head of a lion and the brain of a brick.'

A much more glamorous figure is Captain Louis Nolan, ADC to General Airey, and the man traditionally blamed for the blunder of the Charge.

To a generation of cinema goers he is best remembered in David Hemmings' portrayal of the man whose impetuous gesture to Lord Lucan precipitated the entire Charge of the Light Brigade. How much responsibility he can really take for the disaster is a highly debatable point for which 'Into the Valley of Death' provides at least one answer.

But the cavalry division (like any other) also had on its strength a number of wives who accompanied their men out to the Crimea. These were few, since only one in six of married men were allowed to bring their wives on the expedition, but their presence (often in extreme hardship) should not be forgotten.

One such woman is a major character in Into the Valley of Death - Sally Jarvis, fictional wife to Ryder's infamous Sergeant-Major. Like many other wives she turns from laundry to nursing as a way of supplementing the family income, but Sally has a rather more important role to play than that...

The three Highland Regiments of the 42nd ('the Black Watch'), 79th (the 'Cameron Highlanders') and the 93rd (the 'Sutherland Highlanders') all played a vital part in the first months in the Crimea, and it would have been unthinkable to write about this period without at least one character from their ranks.

Photographs of the time depict the desperate fierceness of the Highlanders, their savage appearence enhanced by the 'Crimean beards' which were almost universal in an army without facilities for shaving. Niall Mackenzie apparently goes against this stereotype, being a young and kind-hearted former stalker from an estate near Strathcarron, but that is before he goes into battle for the first time...

The Highlanders made an unforgettable impact at the Battle of the Alma, after which the Russians nicknamed them the 'devils in skirts'. It still can't have been easy. Many of these men (like Mackenzie) had never before heard a shot fired in anger.

The war-like commander in Gibbs' painting is another important figure in the book - Sir Colin Campbell, commander of the Highland Brigade, whom many believed would have been the best choice to lead the whole army.

He looks decidedly grumpy in most of his portraits, but Mackenzie finds him inspiring - and from the recorded quotations included in the book I find it difficult to disagree.

But the most famous action performed by any Highland Regiment in the Crimea was undoubtedly the stand by the 93rd that gave us the phrase 'The Thin Red Line'. I won't say more of it here, because (of course) it's in the book...

The Guards' Brigade seems one of the most incongruous fighting units in the Crimea. Those immaculate red uniforms and tall black bearskins seem somehow more appropriate to duty outside Buckingham Palace than to slogging up a hill in full kit facing the storm of enemy cannon. Dennis Woodall would certainly agree. Woodall isn't enjoying the Crimea much at all.

Nevertheless, the Crimean War was arguably the Guards' finest hour. The Grenadiers in particular will always be famous for their role in the Battle of Inkerman, where at one point a handful of less than 300 held off a force of 10,000 Russians by themselves. The unit into which the Second Battalion of Grenadier Guards has now been absorbed is known as 'The Inkerman Battalion' to this day.

And if Woodall is an unlikely hero, there are plenty of real ones in the novel. The man depicted carrying the colours in Robert Gibbs' painting above is Lieutenant (later Captain) Henry William Verschoyle, who also brought volunteers to the aid of Sir Colin Campbell at the battle of Balaklava.

He doesn't look very heroic in Fenton's portrait, but to me he looks like a modest, good-humoured young man who simply didn't like being photographed!

There were far too many real-life heroes for me to mention them all in the novel, but I had to include a cameo of Captain Edwyn Sherard Burnaby, whose attempt to save the colours at Inkerman has such consequences for my characters. He would have been only 24 at the time.

Into the Valley of Death is still a work of fiction, and many of the well-known figures of history are only on the periphery of the story.

Lord Raglan, for instance, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in the Crimea, is obviously present, but it would have been highly unlikely for him to interact significantly with my own humble characters - none of whom are even officers.

This was a conscious decision on my part. So much has been written about the decisions made by the commanders in the Crimea, and I wanted to see the other side - the effect of those decisions on the men who actually had to live - and die - with them. I wanted Into the Valley of Death to give us 'a voice from the ranks'.

A Voice from the Ranks is in fact the title given to the memoirs of Timothy Gowing of the 7th Regiment of Foot, the Royal Fusiliers. Gowing's account was invaluable in the writing of this novel, and inspired the creation of my last principal character - Corporal Albert Flowers, known as 'Bloomer of the 7th'.

Bloomer is a very different character from the highly respectable Gowing, and clearly of a very shady past in the London underworld. They share only a regiment, and one which played a very notable part in the Siege of Sevastopol.

The 7th Fusiliers - and Bloomer - have a great deal more to do in the second book in the series. So do my other characters - or, at least, those who survive...